Automation and the Jevons paradox

27 April 2024

I watched a great talk about sustainable AI recently at Services Week 2024. The speaker was software developer Ishmael Burdeau.

He mentioned something called the Jevons paradox. It describes how energy efficiency gains can often lead to more energy usage rather than less.

This was something I'd often wondered about, and I'm very glad to now have a name for the thing.

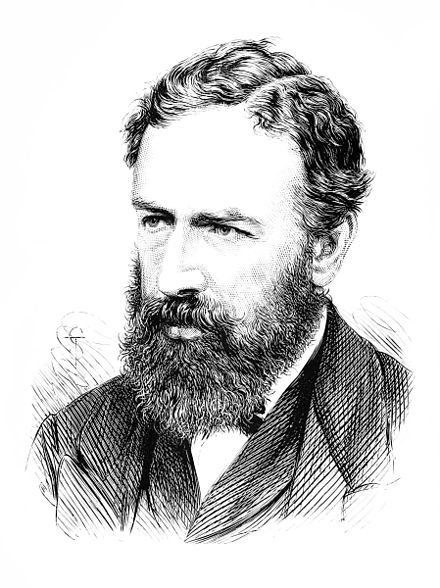

Jevons wrote: "It is a confusion of ideas to suppose that the economical use of fuel is equivalent to diminished consumption. The very contrary is the truth."

He was writing about coal consumption after the invention of the Watt steam engine. But once you know about his paradox you can see the effect everywhere.

For example:

- improving road network efficiency leads to more driving, not less congestion

- increasing crop yields results in more crop production, not less land usage

- building a reservoir leads to more water consumption, not less water scarcity

- improving data centre efficiency leads to more data centres not less energy usage

The effect isn't guaranteed but seems relatively common, especially in scenarios where there is latent, unmet demand for a resource.

In each case, a resource gets cheaper or more efficient, and we use that as an opportunity to consume more of it, rather than save money or conserve it.

To take the car example: adding a lane to a highway will reduce congestion initially. But it'll also make driving a more effective option in comparison to public transport.

People will then switch to driving, eventually bringing congestion back to it's former levels, or higher even.

Only now there are far more cars on the road. There's a kind of ratcheting effect with Jevons where we become ever more dependent on technology. It's hard to go back.

The automation myth #

Anyway, all this got me thinking about a phrase I've heard many variants of during my time in the public sector. It goes something like:

"If we do X, it'll free people up to do more valuable or meaningful work"

Where X is some kind of efficiency gain produced by digital transformation, AI, automation or similar (we say it more often about other people's jobs than our own).

I've been guilty of thinking it myself. I recently prototyped a tool for coverting PDF forms into web forms with these kinds of efficiency gains in mind.

But how often does people's time actually get freed up? Could this be another Jevons-like situation?

It's true that if we reduce how long it takes to do this kind of work, people would in theory be able switch to doing something more meaningful (or work less intensively).

But other things are also possible: we might decide to pay those people less money, hire them less often or just give them loads more of the low value work to do.

In a world driven by cost savings and profit margins, which outcome is more likely?

As a side note - I think we sometimes downplay these 'low value' activities, because they appear repetitive or trivial.

But the real value is what's happening in the minds of the people involved - the ideas they're having, patterns they're spotting, decisions they're coming to.

Tech won't save us #

Ultimately it's not really about the technology, it's about incentives, and a mismatch of values.

Some organisations prioritise making or saving money over improving the environment or delivering better services.

So, if we really want to address this, we shouldn't expect the solution to be technical.

To avoid the Jevons paradox, technological efficiency gains would need to be paired with the right governance, culture, funding, standards etc.

"Good, fast, cheap - pick two" they say. Let's automate to make things better, not just faster and cheaper.

It's complicated #

One more example. AI and automation is often promoted as a way of handling complexity. But handling complexity isn't the same as reducing it.

In fact, by getting better at handling complexity we're increasing our tolerance for it. And if we become more tolerant of it we're likely to see it grow, not shrink.

Again, there's a ratcheting effect as the world becomes more and more complex, and harder for people without access to AI to navigate (Rachel Coldicott and others have been making this point for a while now).

But something that can genuinely reduce complexity, rather than just mask it, is good design.

Good, user-centred design is how we can deliver services with just enough complexity - enough to model the rich diversity of people's circumstances, but no more.

Update: Turns out Benedict Evans has also written a much more detailed and well informed thing on the same subject. You should go read that - it's very good.